In my ongoing effort to remember what I have read, some notes on an excellent, although time-warped, book: Winning Decisions: Getting It Right the First Time; J. Edward Russo, Paul J.H. Schoemaker.

Between Y2K and 9/11

This book was published in late 2001 meaning most of it was written in the late 1990’s and before 9/11 in the United States. As a result, a number of the anecdotes are about companies and organizations that have since disappeared over the past 20+ years.

I wish I could say this book had the secret sauce for making decisions but a) decisions are hard work so there are no short cuts, and b) the book’s methodology only provides a systematized way to work harder. Is this a recommended read? No, if you are busy and searching for short cuts. Yes if you enjoy good anecdotes, excellent end notes and want to have some questions and memory jogs to make better decisions. On the other hand, you can just read this very long blog that has extracted the best bits.

The Methodology

The authors present decision making in four steps:

- Framing or the context of the decision.

- John Dewey: “A Problem well stated is a problem half solved.”

- Gathering intelligence intelligence which includes an assessment of what you don’t know about the decision; consideration of biases.

- Coming to conclusions systematizing decision-making, there is lots of focus on weighted analysis methods.

- Learning from experience so as to get better at making decisions.

Nothing new here other than laying out the process and timely reminders to do things like ‘figuring out the problem being solved before working on the solution’.

Framing – Memory Jogs

“Frames”—mental structures that simplify and guide our understanding of a complex reality—force us to view the world from a particular, and limited, perspective. Frame contextualize a decision. I like this focus and the questions asked are relevant before jumping too far down a solution rabbit hole.

- Frame Strengths and Limitations. Frames filter what we see. They control what information attended to and obscured.

- Frames themselves are often hard to see; they appear complete and simplify the world.

- Frames can be “sticky” and hard to change particularly if there is an emotional attachment to their frames, changing frames can seem threatening.

- Metaphors/frames can highlight important facets but if used indiscriminately it limits options, possibly excluding the best ones from consideration.

- Frame Options, the more options you generate, the greater your chance of finding an excellent one; avoid judging pre-maturely, shift perspective to expand the frame of reference.

Framing – Memory Jogs

- What’s the crux or primary difficulty in this issue? Which of the four stages in the decision process will be most important?

- In general, how should decisions like this one be made (e.g., alone or in groups, intuitively or analytically, etc.)? Where are the organization’s strengths and weaknesses?

- Must this decision be made at all, now, by whom, what parts can be delegated?

- How much time have decisions like this one taken in the past; how long should this decision take? When should it be made, are the deadlines real, arbitrary or negotiable?

- Can I proceed sequentially from framing to gathering intelligence to coming to conclusions, or must I move back and forth?

- Where to concentrate time and resources, how much time is needed on each stage?

- Can I draw on feedback from related decisions and experiences I have faced in the past to make this decision better?

- What are my own skills, biases, and limitations in dealing with an issue like this? Do I need to bring in other points of view? Which other points of view would be helpful?

- How would a more experienced decision-maker, whom I admire, handle this issue?

- Does this decision greatly affect other decisions? If so, what are the cross-impacts.

- What are the three (five, etc.) most important objectives to aim for in this decision?

- What are the yardsticks, reference points, and boundaries inherent in my frame? How might someone in another organization approach these measures?

- Can you frame the decision in an options approach; which options are parallel, mutually exclusive or complementary; how do the options inter-act with each other?

Intelligence Gathering

If frames contextualize the question, intelligence gathering helps you ensure you have the best available information before answering the question. The authors also caution the decision maker about analysis paralysis.

Process for Gathering Intelligence and Considerations

- 1. Ask the most appropriate questions.

- 2. Interpret the answers properly.

- 3. Decide when to quit searching further.

Some intelligence gathering considerations:

- Separate “deciding” from “doing.” Be a realist when deciding; confine optimism to implementation.

- Make it a habit to seek evidence that disproves your favorite theory or desired outcome.

- Never pretend uncertainty is smaller than it is; reduce uncertainty and then manage it.

- Don’t try to pick the one “most-certain” future, generate multiple futures and manage uncertainty.

Decision Biases

Much has been written about biases and the authors do not provide an exhaustive list (although Wikipedia – List of cognitive biases):

- Confirmation bias is the tendency to search for, interpret, favor, and recall information in a way that affirms one’s prior beliefs or hypotheses.

- False efficiency or Anchoring bias the tendency to pay too much attention to the most readily available information, and to excessively anchor opinions in a single statistic or fact that dominates the thinking process.

- Recency or Availability bias is the tendency to think that examples of things that come readily to mind are more representative than is actually the case.

Scenario Construction

Scenarios are one way to avoid the above biases and to generate the optimum solution. This is similar to and discussed in my my blog on ‘Proofs of Concepts‘. The book provides an overview of how to construct scenarios:

- Define the scope. Set the time frame and scope of analysis

- Identify the major stakeholders.

- Who will have an interest in these issues?

- Who will be affected by them?

- Who could influence them?

- Think about each player’s role, interests, and power position, and ask how and why they have changed over time.

- Identify basic trends. What political, economic, societal, technological, legal, and industry trends that affect the issue identified in step 1?

- Identify key uncertainties.

- What events whose outcomes are uncertain will significantly affect the issues you are concerned with?

- For each uncertainty, determine possible outcomes.

- Construct initial scenario themes.

- Select the two biggest uncertainties and two widely different outcomes of each uncertainty.

- Create a 2×2 matrix of scenario themes.

- Check for consistency and plausibility. Are any scenarios generated above implausible, internally inconsistent, or irrelevant?

- Develop scenarios.

- Flesh out themes, rearrange the scenario elements to create two to four relatively consistent, plausible scenarios.

- These scenarios should describe generically different futures rather than variations on one theme.

- Identify research needs. Research needed to flesh out uncertainties and trends.

- Develop quantitative models. Numerically estimating the impact of the trends and uncertainties.

- Evolve toward decision scenarios. Finally, in an iterative process, converge toward two to four distinctly different scenarios that you will eventually use to test your strategies and generate new ideas.

Intelligence Gathering Memory Jogs

Good questions that prevents one from charging off down the solution rabbit hole:

- What’s the single most important piece of information that will enable me to assess the decision options? How can I get it most easily?

- Does the information I need already exist in someone’s files (or in their head)?

- What’s the biggest disconfirming question I can think of, the one that would completely change my decision? How can I most easily get that question answered?

Coming to Conclusions

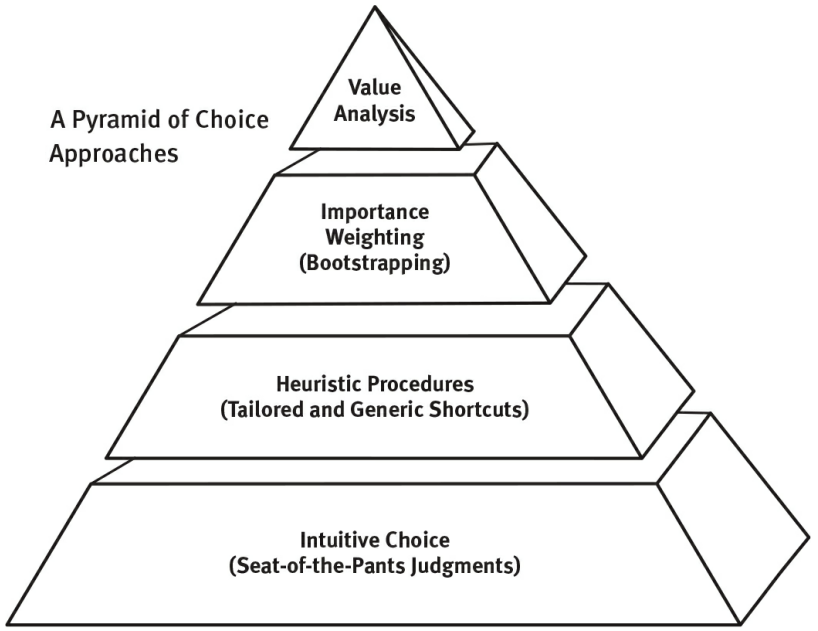

The following pyramid is the authors’ suggested way to approach choices. I am not convinced that the pyramid is comprehensive or that the implied improved value by going towards the top is valid. In other words, I think the pyramid is stilted towards an academic ‘perfect-world’ decision-making process. Nevertheless, as an ideal mental model it does have value.

- Intuitive choice:

- Automated expertise: when the situation matches numerous experiences.

- Often not consistent or best method if situation differs

- Heuristic Procedures

- Provides a clever shortcut through a maze of possibilities.

- Enable the determination of the right answer, or a close approximation, most of the time—without expending a lot of effort in the process.

- Test the heuristic to ensure it is still viable and relevant.

- Importance weighting

- A simple and systematic model of human intuition typically beats intuition.

- Weighting Model

- Make the criteria numeric.

- Assign importance weighting to each factor.

- Compute the analysis.

- Evaluate and improve the model.

- Value Analysis

- More precisely aligns factors to larger organizational values

- Changes in impact is not linear but can be exponential.

- Example of technique: Multi-attribute utility

Group Decisions

The opposite of speaking is not listening, but waiting to speak.

- How well conflict is managed determines whether decision-making groups fail or succeed.

- Moderate task conflict and low relationship conflict is the decision-making ideal. Only then are groups likely to outperform individuals.

- Relationship conflict: between individuals

- Moderate task conflict: differences of opinion about the task at hand and its completion.

- Divergent view management

- Invite dissenters

- Remain neutral as a leader

- Reduce conformance pressure

- Establish norms supporting conflict and creativity

- Establish diverse groups (personalities, perspectives, etc.)

- Give two sub groups the same task

- Use anonymous pre-commitment

- Appoint a devil’s advocate

- Solicit multiple options from group members

- Use minority reports to gain a balanced perspective

- Hold “Second Chance” meetings for important decisions

- Separate facts from values within a group

- Listening to find common ground

- 1. Ask people to listen, without interruption or planning a rebuttal, to the arguments advanced by an advocate of one view. If you doubt the sincerity of the listeners, give them the task of reciting the speaker’s key points.

- 2. Clarify without opinion. Have group members, especially those who disagree, ask the speaker for additional information about why that conclusion was reached.

- 3. Record but not edit the concerns and reasons given. Checking with the speaker to make sure that positions stated are being accurately reflected.

- 4. Designate a speaker for another point of view, and repeat the first three steps. If more than two camps exists, steps one through three can be repeated for each.

- 5. Review these and other people’s concerns, pointing out the areas of agreement. Then ask the group to reframe the question, taking as many concerns from each side into account as possible.

- 6. Test for commonality. To see if a robust solution or at least points of common-ground exist.

- Nominal Group Technique

- 1. Ask individuals to write ideas anonymously

- 2. Collect and record those ideas in terse phrases

- 3. Add ideas and build on the ideas of others

- 4. Discuss each idea for clarification and pros/cons

- 5. Vote privately

- 6. Discuss the vote and revise alternatives.

- 7. Generate a final ranking

Learning

I like the focus on learning not about the decision but instead with a focus on the process. Their list of methods is by far not exhaustive but provides for a basic check list to ensure one is become the best decision maker possible.

- Learning starts with a willingness to learn and to examine the process that lead to a result.

- Techniques to improve learning

- Seek to make the best use of all available information.

- Unambiguously define success beforehand; then measure it.

- Accept accountability and manage in the future past limitations.

- Ask and use feedback from others

- Record and manage learnings

- Attempt to track the path not taken

- Use proofs of concept and ‘fail fast’ to accelerate learning.

- Develop corporate or personal level learning histories

- Conduct self and group learning audits