Engaging post-secondary students in projects comes with enthusiasm and costs. Seven school project success factors are considered which align the various stakeholders. Successful collaborations yield meaningful experiences.

I like working with post-secondary students. Their enthusiasm and energy is refreshing for old farts like me. As well, there is a value proposition for nonprofits, the school, and the student.

- Finding New Blood

- What Kind of Students are Talking About Here

- The Seven Successes of Student Projects Meet Anna Karenina

- Meet the Seven Successes (Anna Couldn’t Be Here Today)

- The Score After Five Projects: Two Happy Anna’s

- Two Annoying Anna’s

- What Happens When Anna Doesn’t Show Up

- Five Steps to Avoid Anna and Have a Successful Student Project

- Notes and Further Reading

Finding New Blood

Nonprofit boards must constantly replenish those who are interested in their ranks. An organization can tell its ‘story’ to a new generation of potential customers, donors, volunteers, or supporters through a student project. Student involvement is up close and personal marketing with a demographic that may otherwise be difficult to reach.

What Kind of Students are Talking About Here

Student work programs come in many shapes and sizes. This was discussed in a previous blog, Schooled in Student Work Experience Definitions which introduced the Work Experience Relationship Model. For this blog, I am restricting myself to the School Project variety, the Classroom Projects found in the bottom left corner of the 2×2 matrix:

A Classroom Project is more than Job Shadowing. One or more students are expected to complete a defined project or perform a set of activities in support of operations. A minimum number of contributed hours is specified (ideally 20 or more for a semester). More time intensive projects might be part of a capstone project for a program or a final grade. In this case, 100 or more hours may be contributed by the students.

The Seven Successes of Student Projects Meet Anna Karenina

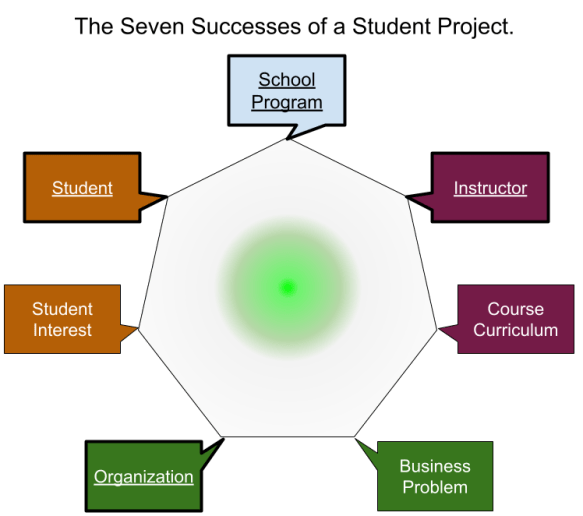

What makes for School Project a success? There are seven factors organized into 3 pairs and one stand alone consideration. One deficient factor may degrade success and compounding problems can create an unhappy project worthy of Tolstoy.

And Tolstoy should know as he gave us the Anna KareninaPrinciple which states that “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Applied to Student Projects, “All successful projects are alike; each unhappy project is unhappy in its own way due to one or more failures of the Seven Success Factors.” [1]

Meet the Seven Successes (Anna Couldn’t Be Here Today)

- 1. Program. This is the structure the school or instructor has created and considers things like expected number of hours to be worked, recruiting community partners, support when things go awry, etc.

- While not strictly necessary, the Program takes work and effort off the other players who are busy with their individual parts.

- The Program should toil in the background and noticed only by its absence.

- 2. & 3. Organization and Business Problem. The first Success-Pair is the Organization hosting the students. Success includes:

- An enthusiastic and available project liaison who explain the business problem, and mentor the students in the context of the organization, industry, and life.

- An interesting, relevant, and REALISTIC business problem to be solved. Neither too daunting nor too irrelevant. Ideally, its resolution should create resume fodder for the students.

- Bonus Successes for the students would be a field trip, wrap up party, parting gifts, etc.

- 4. & 5. Instructor and Curriculum. This Success-Pair matches the course content with a link to real world relevance.

- The Instructor should WANT the project in their classroom.

- The Curriculum must be relevant to the external organization and the business problem.

- 6. & 7. Students and Their Interests. Last and some ways least are the students. This the group that has the least say in School Project; in essence they are a captive audience. Nevertheless…

- Students must be treated with respect and their enthusiasm channelled.

- They have many competing demands on their time and a work experience project may be the thing de-prioritized if they are feeling used, ignored, or are simply not having fun.

- The community organization must align how their project aligns and supports a student’s future academic and career aspirations.

- One of the ways to create alignment is resume context – how will this project get you a job or help you with a school admission?

The Score After Five Projects: Two Happy Anna’s

In the last two years, I have run five student projects. Two of them were very successful and with a happy outcome. The curriculum, business problem, instructors, and students all aligned in a happy ‘Anna Karenina’ sort of way.

Two Annoying Anna’s

Two projects had annoying challenges for me. In one case, the instructor criticized the results even though this team was the only one with a successful project. In another, the curriculum intruded on the business problem. The solution had to be modified to better support the course content. In the end, not a big deal but an example of the curriculum-tail wagging the business problem-dog.

What Happens When Anna Doesn’t Show Up

The final example of a project gone wrong had a ‘sort of’ happy ending but could have been an unmitigated disaster for the students.

Of a team of four students, one individual was not just coasting but was closer to being a parasite on the work of the other three. An eight-month capstone project, it took the team nearly five months to eventually kick this person out. Subsequently, the remaining members produced a satisfactory result. Fortunately, the Program and instructor supported this decision which otherwise could have imperiled the remaining students ability to graduate.

Five Steps to Avoid Anna and Have a Successful Student Project

The key take aways from my most recent experience and thinking about the Seven Successes of a Student Projects are as follows:

- Pick the Right Program. Most organizations have business problems related to mundane things like accounting, legal-issues, technology, etc.

- Ensure the program has courses related to your business problem.

- If absent, ask for such courses to be added or pick a different program/school.

- Pick a Goldilocks Problem. Not too big, too complex, too long, nor too simple.

- Something that the students can realistically complete in the hours and time and skills available.

- When in doubt, err on the side of a smaller problem.

- Evaluate the Students Quickly. Particularly for a single semester project, decide if working the students are worth the bother.

- 99.9% of the time, the students will be a lot of fun and a joy to work with.

- Statistically, if you run enough projects, you will eventually run into the 0.01%.

- Work with the Program and Instructor to remediate the problem or abandon that project.

- Build a Rapport with the Instructor. Make the life of the person teaching the course as easy as possible.

- Help them with enthusiasm for the project component of the curriculum and find ways to demonstrate that what they are teaching has relevance in the real world.

- Have Fun and Enjoy the Enthusiasm. It is impossible for each of the Seven Successes to be perfect for each project.

- Roll with the punches, treat everyone in the process with the respect they deserve, and have fun with the students – they will keep you on your toes!

Notes and Further Reading

- Profuse apologies to Leo Tolstoy and his 1877 novel Anna Karenina. The principle outlined has since taken on wider adoption: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anna_Karenina_principle.

Pingback: Student Opportunities – 2025 | SAPAA

Pingback: 2025-06-12 Grant MacEwan PM Capstone Introduction | SAPAA