Reflecting on six months of volunteer efforts tracked through the IPOOG methodology. While tracking one’s time is challenging, it does help with self-reflection and understand the efforts required to take on major projects. Important information for both a volunteer organization and the volunteer.

Continue readingTag Archives: planning

An Idea to Insure an Interesting Year

A very ambitious ‘Event-Idea’ which will help nonprofits, senior volunteers, and even small businesses answer the question: “What type and how much Insurance do we need?”. This post is a placeholder to get some potential ideas.

Continue readingSystematically Herding Cats and Volunteers on May 28, 2024

When does a volunteer management system make sense to a non-profit organization? This lunch-time Webinar will provide a survey of VMS systems and features.

Continue readingChecklist Manifesto

In my ongoing effort to remember what I have read, some notes on Atul Gawande’s book, “The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right” [1].

Continue readingUsing the Now-Event Map

In my last blog, I introduced the ‘NOW-Event-Map‘. This model combines both a forward looking strategic planning model with a retrospective performance reporting model. At the center of the map is the enduring concept of ‘NOW’. At the end of the prior blog I promised some thoughts on how the map might be used – besides as an academic thought exercise.

PRMM – How is That Planning Thing Working Out for You?

This is the second in a series of blogs on a Practical Risk Management Method or PRMM. At the bottom of this blog is a refresher of the other steps. This step’s premise is don’t separate your planning activities from your risk management activities. In other words:

Planning = Risk Management. Planning is ultimately about managing uncertainty which is a fancy name for Risk. At this point you may be saying:

- Of Course: we already do this. Good on you, see you at the next blog!

- Great Idea: this may be incrementally more work during the planning process but ultimately over all less effort for the organization.

- What is This Planning Thing you Speak Of: hmmm, we may have identified your top risk.

I am afraid I can’t help you if you fall into the last category but hopefully these blogs can help you if you with the first two.

Continue readingAnti-Fragile Risk Management (ARM)

This is part two of my thoughts on Risk Management. Part I, “Guns, Telephone Books and Risk” focused on the problem of creating long lists of things that will (may) never happen.

Continue reading90 or 99 – That is the Strategic Question

Nicolas Taleb would have us believe that strategic planning is ‘superstitious babble’ (see Anti-fragile strategic planning). In contrast, Kaplan and Norton make strategic planning a cornerstone of the Balanced Scorecard. The reality is probably in the middle.

This blog however considers the question, how much time should an organization spend on planning? Successful or not, when do you cut your losses for a year or when do you think that you are not doing enough?

How Much Is Enough?

On the one hand, strategic planning can become its own self-sustaining cottage industry. Endless meetings are held and navels are closely examined with little to show for it. On the other hand, the organization is so tied up in operations and ‘crisis du jour‘ that they wake up and discover the world (and even their organization) has completely changed around them.

What rule of thumb or heuristic can be used to know that you are doing enough Strategic Planning without decorating cottages? My proposed answer is somewhere between the 1.0% and 0.1%. Although a full order of magnitude separates these values, a range is important due to the volatility of an environment an organization finds itself in. Governments are likely on the low-end (closer to 0.1%) and tech start-ups on the higher end (1.0%).

For more on the basis for these heuristics, take a read of ‘A Ruling on 80, 90 and 99‘ for my thoughts and a review of such things as Vilfredo Pareto’s legacy and internet lurkers. A recap from this blog is as follows:

- Pareto: 20% of an organization’s actions account for 80% of its results.

- 90 Rule: 1% of the operational decisions are enacted by 9% of the organization affecting the remaining 90%.

- 99 Rule: 0.1% of the strategic decisions are enacted by 0.9% of the organization which impacts the remaining 99%.

Thus the 99 Rule provides a minimum amount of time for an organization to consider strategic questions while the 90 rule provides a maximum amount of time.

Who Does What and What to Do with Your Time?

Consider a fictional organization of 1,000 people. This is a medium sized business, typical government Ministry or employees of a large town or a small city. Assuming there is about 1,700 productive hours on average per year per employee (e.g. after vacation, training, sick time, etc. see below for my guesstimation on this) this means the organization in total has 1,700,000 hours to allocate. How much of this precious resource should be spent doing strategic planning?

I am recommending no less than 1,700 hours and no more than 17,000 hours in total. In total means involving all people in all aspects of the process. Thus if there is a one hour planning meeting with 20 people in the room, that is 20 hours. To prepare for this meeting, 3 people may have spent 2 full days each – another 3 x 2 x 8-hours or another 48 hours against the above budget.

Measuring what Matters

The point of completing these measurements is to answer four fundamental questions:

- Is the organization doing enough strategic planning relative to the environment?

- Is the organization doing too much planning?

- Are we getting value for the investment of resources?

- How do we get better at the activities to reduce this total?

Is the organization doing enough strategic planning relative to the environment?

What happens if you discover you are not doing enough? For example your 1,000 person organization is only spending 100 hours per year doing planning. You may be very good and efficient and if so bravo to you and your planning folks! On the other hand, you may be missing opportunities, blind sided by challenges and mired in the current day’s crisis – in which case maybe a bit more effort is needed.

Is the organization doing too much planning?

The 1,000 person organization may also be in a Ground Hog Day’esque hell of constantly planning with not much to show for it. Perhaps you have a full time planning unit of five people who host dozens of senior management sessions and the best they can is produce an anemic planning document that is quickly forgotten. In this case, measuring the effort of consuming 10 to 20 thousand hours of efforts for nought can lead to better approaches to the effort.

Are we getting value for the investment of resources?

The above two examples demonstrate how a bit of measurement may help you decide that 100 hours is more than sufficient or 20,000 hours was money well spent. The output of the planning process is… well a plan. More importantly it is a culture of monitoring, planning and adapting to changing organizational and environmental circumstances. Thus setting an input target of planning to measure the quality of the output and the impact of the outcomes can answer the question if the planning effort were resources well spent.

How do we get better at the activities to reduce this total?

The advantage of measuring, evaluating and reflecting on the planning efforts is to get better at. Setting a target (be 1.0% or 0.1%) is the first step of this activity and measuring against this target is the next.

Good luck with your planning efforts and let me know how much time your organization spends on its planning initiatives.

* How much Time Do You Have?

How much time does an organization have per annum to do things? The answer is … it depends. Here are two typical organizations. The first is a medium size enterprise that works an 8-hour day, offers 3-weeks vacation per year, in addition to sick days and training (e.g. for safety, regulatory compliance, etc.). On the other hand is a Ministry that offers a 7.25-hour day, 5-weeks of vacation plus sick and training days.

| Organization | Medium Size Company | Government Ministry |

| Hours/day (1) | 8 hours | 7.25 hours |

| Work days per year (2) | 254 | 250 |

| Work Hours per year | 2,032 | 1,812.5 |

| Avg Vacation days x work hours (3) | 120 (3 weeks) |

181.25 (5 weeks) |

| Avg Sick Days/year x work hours (4) | 60 (7.5 days) |

54 (7.5 days) |

| Avg Hours of Learning/year (5) | 42 | 29 |

| Total productive hours/employee | 1,810 | 1,548.25 |

- Few professionals work an 8-hour day let alone a 7.25-hour one. Nevertheless, everyone has non-productive time such as bathroom breaks, filling up on coffee, walking between buildings. So I am leaving the actual average productive hours at 8 and 7.25 respectively.

- For a cool site in adding this calculation, see: www.workingdays.ca. Note this includes 3 days of Christmas Closure.

- 10 days is the minimum number of vacation days required to be given to an employee. The average is a surprisingly difficult number to find (at least to a casual searcher). 15 days is based on an Expedia 2015 survey.

- Reference Statistics Canada: Days lost per worker by reason, by provinces.

- Sources vary. I have chosen the high value for the for-profit organization as they often have stringent regulatory requirements for health and safety training. For government I have chosen a medium value. Sources:

- 2014 Industry Training Report.

- The Conference Board of Canada’s Learning and Development Outlook.

Other Thoughts on Strategic Planning

Can We Stop and Define Stop?

This week I will be going into an operational planning meeting. Like most of the operational planning meetings I have attended, three questions are being asked:

- What do we want/need to start doing

- What do we need to continue to do or finish and

- What should we STOP doing?

The first two questions are relatively easy to answer and there is a plethora of information on How, Why, When, Where and What to plan. In this blog, I want to focus on the Stop question, specifically:

What does “Stop” Mean in the Context of Operational Planning?

How Many Stops have been Really Stopped?

In my career, I have been in dozens of planning meetings and I cannot really recall something identified as ‘should be Stopped’ that was actually stopped. At the same time, over my career, I have stopped doing many things that I used to do with out the ‘thing’ being part of a planning meeting. Why is it so hard to identify a process to stop and then actually stop it?

Stopping to Define A Process

A quick stop for a definition and in this case the word ‘Process’ which is one of these wonderfully loaded terms. Fortunately the good folks at the International Standards Organization can help: (source: http://www.iso.org, ISO 9000:2015; Terms and Definitions, 3.4.1, accessed 2016-04-02):

3.4.1 process: set of interrelated or interacting activities that use inputs to deliver an intended result (Note 1 to entry: Whether the “intended result” of a process is called output (3.7.5), product (3.7.6) or service (3.7.7) depends on the context of the reference.).

Assuming that an organization wants to stop a process, the challenge of doing so is built into the definition – when you stop something, you must deal with the inputs, the outputs and the impact on the inter-relation between potentially numerous activities.

Starting to Use a Process Focused Way of Stopping

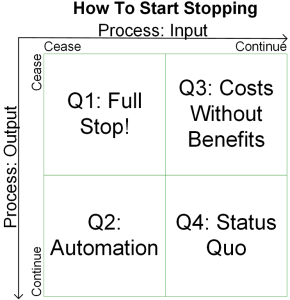

Fortunately the above definition also gives us a methodology to evaluate what processes we can stop, change or that we are stuck with. The Process Focused Way of Stopping uses a 2 x 2 matrix which asks two simple questions: will Inputs or Outputs Cease or Continue? Inside the resulting matrix is a gradient between the extremes of fully stopping or continuing to deploy inputs and outputs. The four themed quadrants can help an organization understand the challenges and execution of stopping a process and interrelated impacts on the organization of doing so.

The Four Quadrants of Stopping

Or how to manage the “Law of Unintended Consequences“.

- Full Stop!:

- Inputs Stop, Outputs Stop

- Business Example: Nokia, formerly a pulp and paper company that evolved into an electronics/cell phone company.

- Organizational thoughts: abandoning or decamping from a process.

- Risks/challenges: if a downstream process requires the output, a new and not necessarily better process may spring up to fill the void

- Automation:

- Inputs Stop, Outputs Continue

- Business Example: Automation of airline ticketing and reservation systems over the past 40 years.

- Organizational thoughts: automation is central to productivity enhancements and cost savings.

- Risks/challenges: over automation can backfire, for example, being able to talk to a human is now seen as premium support for a product instead of simply directing customers to a website or a phone response system.

- Costs Without Benefits (Yikes!):

- Inputs Continue, Outputs Stop

- Business Example: A mining company paying for site remediation long after the mine has been closed.

- Organizational thoughts: Generally this is the quadrant to avoid unless there is a plan to manage the risks and downside costs (e.g. a sinking fund).

- Risks/challenges: Organizations may land here as a result of the Law of Unintended Consequences..

- Status Quo:

- Inputs Continue, Outputs Continue

- Business Example: any company that stays the course in their product line; this includes companies that should have changed such as Kodak.

- Organizational Thoughts: this is a typical reaction when asked to changed processes. Lack of organizational capacity and willingness to change supports general inertia.

- Risks/challenges: As Kodak discovered, a lack of willingness to internally cannibalize and prune an organization may lead to external forces doing it for you.

How to Start Using a Process Focused Way of Stopping?

‘So What?’, how can this model be used? At a minimum I plan to bring it with me to the next planning session and when someone identifies an activity to ‘STOP’ I will point to the quadrant the thing falls into. This is not to prevent good organizational design, new ideas or planning; but it is to focus on the practicalities of planning and execution.

Limits of the Model

The model has its limits. The first is that is micro-biased. It assumes the organization, processes, outputs, and the like remain relatively constant. If your company is bought and the division shut down, the model is mute. The other limitation is technology. AI is seen as an automation tool but what happens when it becomes a game change at the macro level.

Nevertheless, hopefully you can start using this Stopping Model the next time you begin a planning meeting!

Budgeting 2×2

There are two inherent tensions when it comes to budgeting: compliance versus cooperation and people versus technology.